Disturbance

The balance of nature has been disturbed.

The three largest wildfires in Colorado’s history burned in 2020, setting aflame nearly 700,000 acres. In the summer of 2021, the American West was considered to be experiencing the worst drought in modern history.

This project raises questions about the future of snow and its impact on drought and wildfires. By dividing it in three sections - Biophilia, Disturbance, and Water In The West - I explore human innate connection to the environment, and merge scenes of beauty and destruction as if they were part of one continuous landscape, showing how everything in nature is connected. Additionally, I capture abstract photographs of familiar landscapes that are vulnerable to environmental changes. I document the subject through a variety of different exposure times, challenging our perception of reality. Climate change is something that happens over time, and is hard to make sense of in a single photograph. By shooting long exposures of moving clouds and flowing rivers, I blur the lines between time and space, thus relating to the passing time that is the essence of understanding climate. The different technical approaches in this project were my explorations of expressing grief about the changing environment. Metaphorically, the long exposures also relate to the slow, drawn out actions by the world’s governments on implementing solutions to the climate crisis.

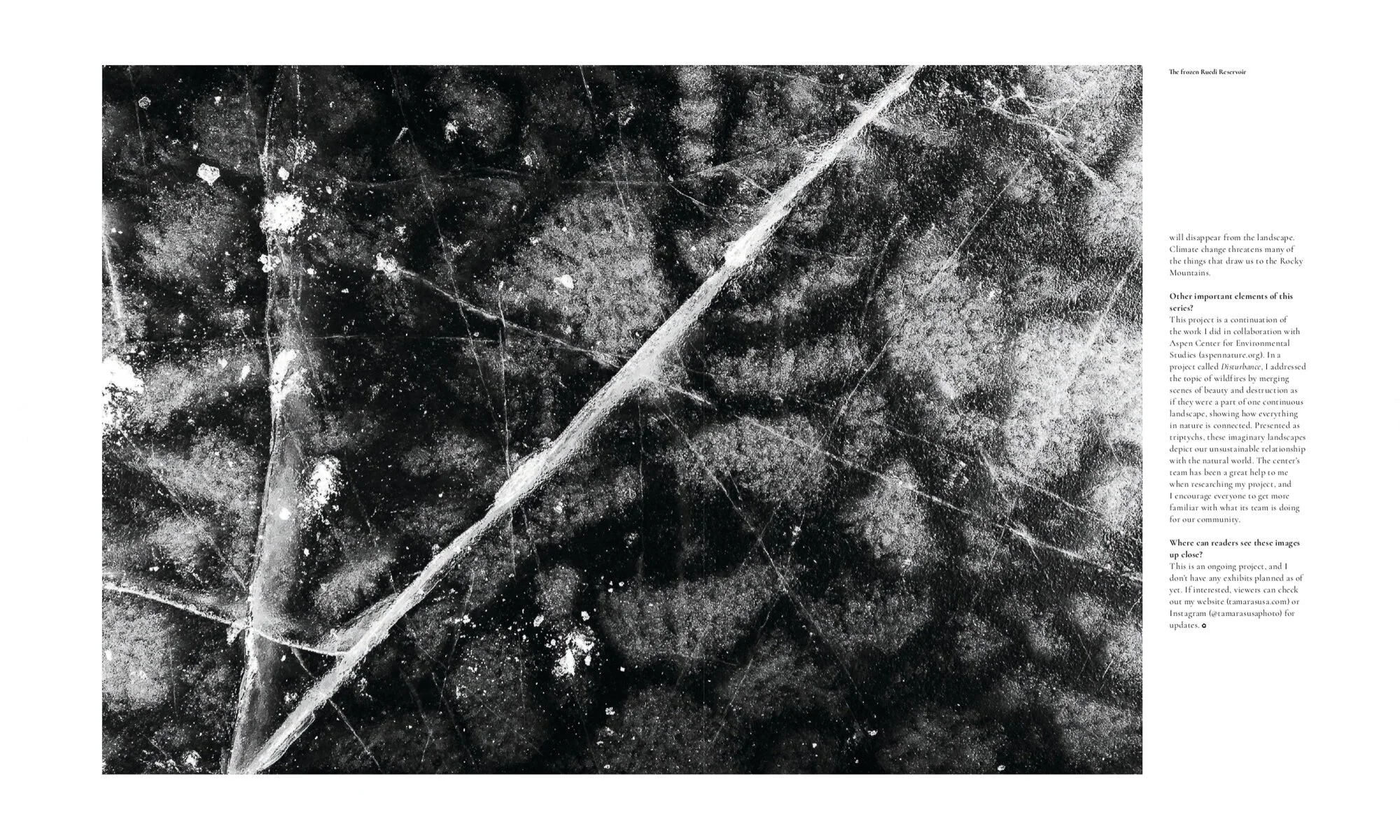

With an average altitude of about 6,800 feet above sea level, Colorado is the highest state in the contiguous USA. Of particular importance is its position in the middle of the continent, which gives it the arid, high-desert climate even though it boasts 59 peaks that rise over 14,000 feet. As a result, the region doesn’t receive much precipitation in the warmer months. Thus, it greatly depends on winter storms to accumulate snow high in the mountains, and act as frozen reservoirs throughout spring and summer.

Even though I specifically focus on the Roaring Fork River basin in my photographs, this information applies to all of Colorado’s Rockies - climate change has shifted the timing of spring, and with the winter snow melting earlier, wildfire risk is expected to rise. This will also have consequences for water resources and ecosystems.

Winters in Colorado are already a month shorter than they were 50 years ago and the Roaring Fork Valley has suffered from major fires two years in a row. In 2020, Grizzly Creek fire burned in Glenwood Canyon, where the Roaring Fork river meets the Colorado river. In 2019, Lake Christine fire burned in the hills of Basalt mountain, causing evacuations of hundreds of people from their homes. As the world warms, the fires will burn more often and more intensely.

Bearing witness to the changing landscape takes a toll on mental health and well-being. It has even been described in psychological terms as eco-anxiety, the chronic fear of environmental doom. As I watched the ashes fall out of the sky and prevent us from doing any outdoor activities, I wanted to find a way of conveying these issues through my photographs in a way that is meaningful to the viewers. People often think of climate change as a “distant issue in both time and space”. The recent fires show that the issue is here, happening in real time, in the place we live, and we can’t look away anymore.

Philosopher Glenn Albrecht proposed the term soliphilia to express the feeling we experience when we are engaged in the politics of a place we love. This association with positivity and interconnectedness is the optimistic outlook on the future that I have based my work on. Instead of showing only devastating impacts of climate disasters, I decided to focus on landscapes vulnerable to environmental changes and show what we are at stake to lose. These photographs invite to see the beauty of our landscapes, and hopefully ignite the need to protect.

Disturbance at the red brick center for the arts, December 2022-february 2023:

Disturbance at ACES, December 2021:

The photographs in this installation were printed on eco-friendly paper, mounted onto hardboard with wheat paste (made out of flour and sugar) and the information is written on the boards with chalk.

This art is not meant to be permanent, as it relates to the ephemeral nature of existence. The prints will degrade over time as they are exposed to wind, sun, snow, and effects of climate change.

in the press

Water in The West was featured in May 2021 Issue of Modern Luxury Aspen Magazine, The Art Edition.

Interview for Aspen Magazine:

What prompted you to take on this beautiful project?

I wanted to do more with my photography than simply take photos of pretty landscapes. I want to seduce the audience with the beauty of our environment, but also remind them of the urgency of protecting this place we all love so much. There’s this general perception that the impact of climate change isn’t an immediate concern. I wanted to bring this topic closer to home and specifically focus on the importance of the snowpack in order to fight wildfires.

Why did you choose water as your subject to convey your message about climate?

Water, in all of its phases, is the most basic physical source of life, and it’s obviously critical to the world’s ecosystems. In Colorado, we don’t get much precipitation in the summer, so we depend on the snowpack to feed the rivers, keep soils moist and protect against wildfires. As much as 75% of water in the West comes from snowmelt. Snow stores water high in the mountains until it’s needed later in the year. As the world warms, less snow impacts our year-round lives in Colorado. Our culture thinks of water as a commodity, but that might not be the case if the climate change continues unabated—it won’t be around.

How long have you lived in Aspen, and what environmental changes have you seen?

I moved to Aspen in 2012. I haven’t lived here long enough to see the climate change, but the winters were already well on their way to being shorter than they were 50 years ago. Since I’ve lived here, we’ve had many Decembers without much natural snow. The Lake Christine and Grizzly Creek fires burned in our vicinity. Most summers, we’ve had fire restrictions and, at times, even water restrictions. Climate change will only make matters worse.

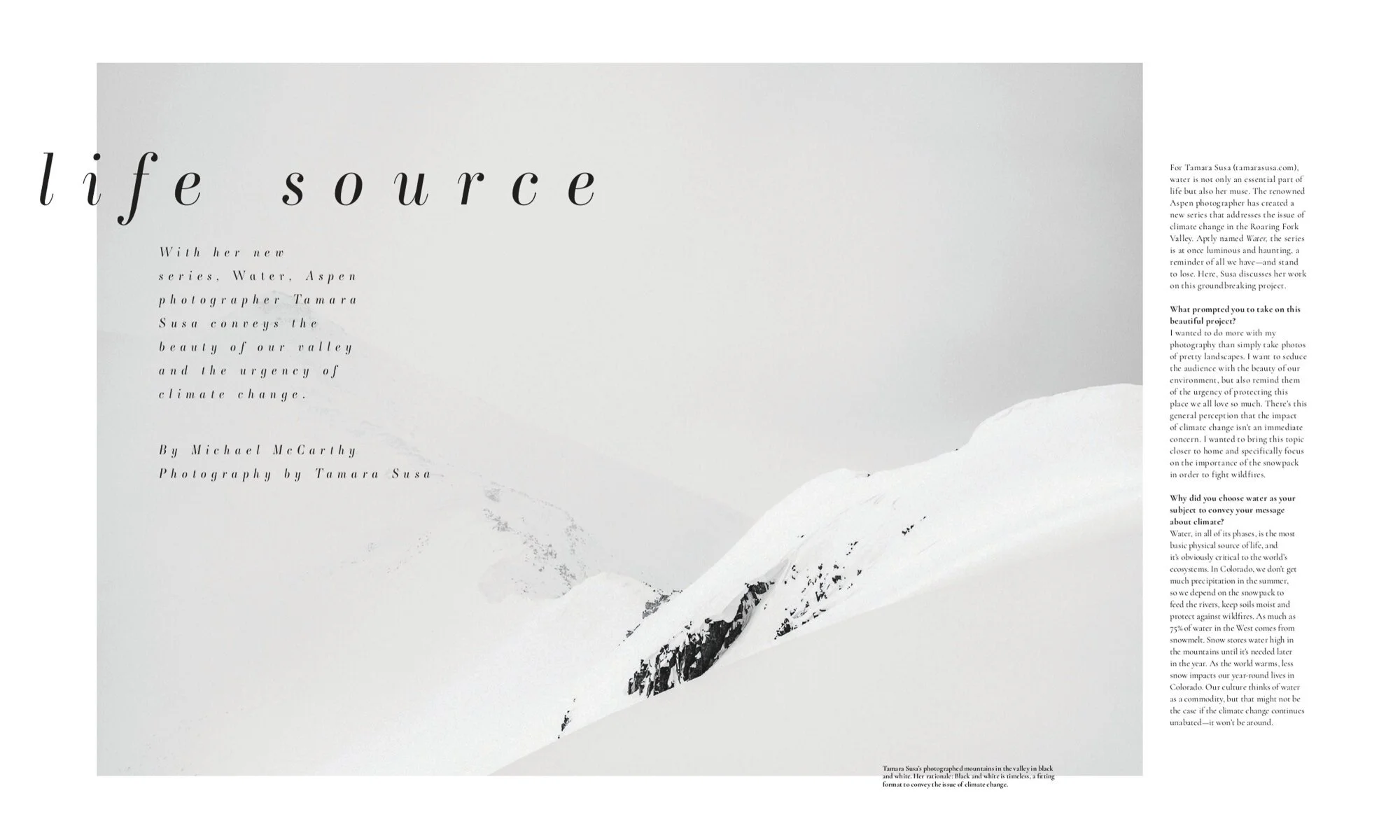

Why did you choose black-and-white photography to showcase your work?

Black-and-white photographs are timeless, which I found fitting when conveying the issue of climate change. The lack of color eliminates distraction and makes us look at nature in a different way. We have some of the most photographed and iconic locations in the country in our backyard. I wanted to step away from cliched photographs and create work that’s a personal expression. I used long exposures to represent the passage of time and lack of implemented solutions to the climate-change crisis.

When looking over what you'd shot for the project, what most surprised you?

I was more surprised by the information I came across while researching the project, rather than the visual part of it. It’s astonishing that people don’t think we’re directly contributing to climate change. At the same time, 84% of wildfires in recent years were started by humans, and three of the largest wildfires in Colorado history burned in 2020. During the second half of this century, fires are expected to burn as much as three times larger than in the first half. With less snowmelt, fighting forest fires will be more difficult.

What do you hope our readers will take away from these images?

Climate change is still an abstract concept to many people. By telling a local story, I hope to bring the issue closer to those who enjoy winters in our mountains—snow isn’t merely wonderful for winter recreational purposes, but also is a crucial water supply for our lives, year-round, in Colorado. As the ski seasons become shorter, low water levels will make rafting almost nonexistent. Mountain-biking trails will turn into dust, forests will turn gray, and wildlife will disappear from the landscape. Climate change threatens many of the things that draw us to the Rocky Mountains.

Other important elements of this series?

This project is a continuation of the work I did in collaboration with Aspen Center for Environmental Studies (apennature.org). In a project called Disturbance, I addressed the topic of wildfires by merging scenes of beauty and destruction as if they were a part of one continuous landscape, showing how everything in nature is connected. Presented as triptychs, these imaginary landscapes depict our unsustainable relationship with the natural world. The Center’s team has been a great help to me when researching my project, and I encourage everyone to get more familiar with what its team is doing for our community.

Where can readers see these images up close?

This is an ongoing project, and I don’t have any exhibits planned as of yet. If interested, viewers can check out my website (tamarasusa.com) or Instagram (@tamarasusaphoto) for updates

research

Information provided with this project is based on research on topics of climate change, health benefits of exposure to nature, and ways to take action. Below you can find links to the research materials. As this is an ongoing project, we will update this page with any relevant information.

Flames in Our Forests: Colorado’s Unprecedented Wildfire Season

By Adam McCurdy, ACES Forest & Climate Program Director

By Adam Corner, Research Director, Climate Outreach; Honorary Research Fellow in the School of Psychology, Cardiff University Robin Webster, Researcher, Climate Outreach Christian Teriete, Communications Director, Global Call for Climate Action

By Matilda van den Bosch and William Bird

3 of the largest wildfires in Colorado history have occurred in 2020

By Minyvonne Burke, NBC News

Trump’s plan for managing forests won’t save us in a more flammable world, experts say

By Sarah Kaplan and Juliet Eilperin, Washington Post

In 48 Hours, Colorado's Wild Weather Sets Records For Both Heat And Snow

By Michael Elizabeth Sakas, NPR News

Five charts that show where 2020 ranks in Colorado wildfire history

By John Ingold, Colorado Sun

Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests

By John T. Abatzoglou and A. Park Williams

Want to make a difference? get familiar with these organizations:

https://protectourwinters.org/

Protect Our Winters (POW) helps passionate outdoor people protect the places and lifestyles they love from climate change. POW is a community of athletes, scientists, creatives, and business leaders advancing non-partisan policies that protect our world today and for future generations.

Aspen Center for Environmental Studies (ACES) is a nonprofit environmental science education organization. ACES has worked since 1968 to inspire a life-long commitment to the earth by providing immersive programming for all ages.

As one of the largest watershed organizations in Colorado, Roaring Fork Conservancy serves residents and visitors throughout the Roaring Fork Valley through school and community-based Watershed Education programs and Watershed Science and Policy projects.

Read more about Colorado’s snowpack and its impact on water resources:

https://www.aspentimes.com/news/hot-dry-conditions-produce-another-active-wildfire-outlook-for-colorado/

https://coloradosun.com/2021/04/06/snowpack-west-melting-earlier-than-20th-century/

https://www.colorado.edu/ecenter/energyclimate-justice/general-energy-climate-info/climate-change/impacts-colorado

https://www.aspennature.org/blog/flames-our-forests-colorado%E2%80%99s-unprecedented-wildfire-season

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/3-largest-wildfires-colorado-history-have-occurred-2020-n1244525

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/03/burger-water-shortages-colorado-river-western-us/

https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2005BAMS...86...39M/abstract

https://climate.colostate.edu/climate_long.html

https://www.cnbc.com/2019/03/20/climate-change-is-taking-a-toll-on-the-20-billion-ski-industry.html

https://www.aspennature.org/blog/secrets-and-science-snow-surviving-or-thriving-through-winter-season

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2019/08/snow-droughts-coming-to-winters-western-us-california-water/

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/west-snow-fail/

https://coloradosun.com/2020/10/20/colorado-largest-wildfire-history/?utm_campaign=buffer&utm_content=buffer9ba6a&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com

https://www.watercalculator.org/footprint/importance-mountain-snowpack-water/

The benefits of nature experience: Improved affect and cognition

By Gregory N. Bratman, Gretchen C. Daily, Benjamin J. Levy, James J. Gross